VIDEO:

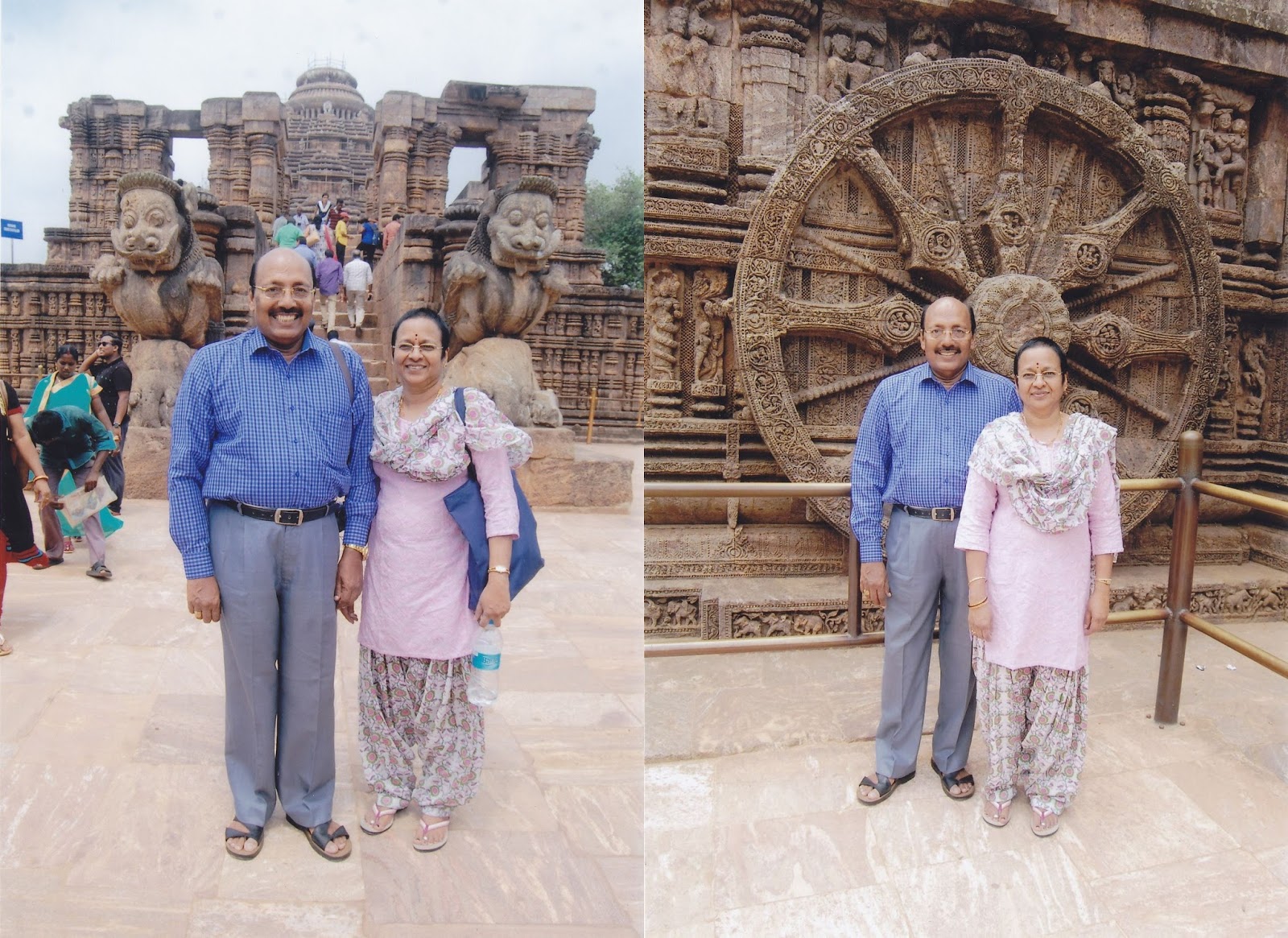

The great Sun Temple at Konark was conceived as a colossal

chariot of the Sun God, Surya, with twelve pairs of exquisitely carved wheels,

drawn by seven galloping horses as if emerging from the turbulent waters of the

Bay of Bengal. The Temple is located in Konark, a small town in the Puri district;

it lies on the coast by the Bay of Bengal. It is connected by road to both

Bhubaneswar (65 km) and Puri (35 km). We visited this divine, historic and

awesome place recently from Puri, as a part of our Orissa (now Odisha) Golden

Triangle pilgrimage.

Even in its present state (it lost its soaring tower long ago),

the temple stands in majestic solitude beyond a vast stretch of golden sand.

The stupendous size of this perfectly proportioned structure is matched by the

endless wealth of decoration on its body – from minute patterns in bas-relief,

executed with a jeweller’s precision, to boldly modelled, free-standing

sculptures of an exceptionally large size. As you read this article you must refer

to the attached photographs and see the attached video to better understand and

appreciate this historic Temple.

The name Konark or also called Konarak is derived from the

name of the presiding deity and means Arka or Sun of the Kona or

corner. Early European mariners referred to the Main Temple as the Black

Pagoda, as opposed to the White Pagoda (the white-washed temple of Jagannath)

at Puri. Both were important landmarks on their voyages in the Bay of Bengal.

Konark Sun Temple was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in

1984, not just for its architectural and sculptural excellence, but also

because it is an outstanding testimony to the 13th-century kingdom of Odisha and a monumental example of the personification of divinity. And

for a long, this Temple is considered to be one of the seven wonders of India.

According to ancient texts, the temple was built by Samba, the

son of Lord Krishna and his wife, Jambavati. The handsome Samba was cursed by

his father for an act of impropriety and became a leper. After twelve long

years of penance to Surya, he was cured and decided to build a temple to honour

the Sun God.

According to Bhavishya Purana, Samba brought Maga families (the

Magi Sun-worshippers of Iran) from Sakadvipa, because local Brahmin priests

refused to worship the image. Alien features, like boots, on the Surya images, are an influence of these immigrants.

The original locale of the episode was probably on the banks of

the Chandrabhaga (modern Chenab) in Punjab, a spot that came to be known after

Samba as Mula-Sambapura, identified with modern Multan (in Pakistan). In fact,

the Sun Temple of Multan finds a glowing description in the 7th-century

accounts of the Chinese chronicler Hieun Tsang.

The shifting of the legend to Konark took place when this area

became a centre of Sun worship. A shallow pool of water, within 3 km of the

temple, is known as Chandrabhaga, and pilgrims take a ritual dip in it even

today.

Historically, King Narasimhadeva I of the Ganga dynasty (1238-64)

built the temple, locally called Surya Deul. It is said that twelve hundred men

worked to complete it in 16 years. As a copper plate inscription of his son, Narasimha

II, states with pride, “King Narasimha built a Mahakutira (great

cottage) of Ushnarasmi (Surya) at Trikona”. Some scholars surmise that

the temple was erected as a memorial by the ambitious monarch after a

victorious military campaign against the Muslims.

Abul Fazl, the chronicler of Akbar (1556-1605), paid tribute to

its colossal grandeur when he wrote in the Ain-i-Akbari: ‘Even those

whose judgement is critical and who are difficult to please stand astonished at

its sight’. In the early 17th century when the Mughals ruled the subah of

Odisha, the image of Surya was removed to a shrine within the precincts of the

Jagannath Temple in Puri. In the 18th century the Aruna Stambha, the pillar

dedicated to the Sun God, was removed to Puri by the Marathas who planted it at

its present site, in front of the temple of Jagannath.

Forsaken by the presiding deity, the temple crumbled through

neglect and decay. The lofty tower over the sanctum collapsed, and by the

mid-19th century, when archaeologist James Fergusson visited the site, most of

the plinth and the exquisite wheels and horses were engulfed by rising sand

from the sea.

Debala Mitra writes that it was not just the cruel forces of

nature, the temple also suffered at the greedy hands of man. The king of

Khurdah removed some sculptures to decorate his own fort, while local people

removed the fallen stones with alacrity.

Extensive steps were taken for the conservation of the temple by

the British government from the beginning of the 20th century. The removal of

sand and debris revealed the grandeur of the temple complex for the first time

in centuries. The initial task of conservation, essential for rendering the

monument stable was completed by 1910. At the same time, a large-scale plantation

of trees was undertaken between the temple and the sea to check the advance of

drifting sand. Since 1939, the Archaeological Survey of India has been doing

continuous work at the site.

The Sun Temple is the finest example of the Odisha style of

temple architecture that includes such fine masterpieces as the Lingaraja

Temple in Bhubaneswar and the Jagannath Temple in Puri.

The seven horses of the Sun Temple symbolise the days of the

week, and the twelve wheels, the months in a year. The resemblance to a chariot

ends with the wheels and the horses; the rest of the temple follows the

traditional plan for Odisha temple architecture, consisting of the rekha

deul or sanctum, originally topped with a tower or shikhara, that

ended in a rounded pyramidal curve. This is connected to the assembly hall, the

jagamohana. At a slight distance from the jagamohana stands the

pillared hall of the bhoga mandapa where offerings were made to the

Gods.

It is the exquisite carvings on the outer walls of the structures

at Konark and the free-standing sculptures that give the temple its unique

character. Every carving was designed to blend in with the architectural plan

of the Surya Deul, creating a temple that is both a brilliant architectural

design and a composite showcase of magnificent sculpture.

Among the statues are huge war horses straining at their reins,

rampant elephants and lions that show great vitality. In contrast, are the

subtle charms of nymphs, dancers, the mithuna or erotic couples in

various moods of lovemaking and the sensual alasa kanyas or indolent

damsels. Royalty can be seen in processions, parades and hunts.

The exquisite Wheels of the Sun Temple Chariot

carved on the face of the Jaganmohan platform are so realistic that they even

have an axle kept in position by a pin as it would be in an actual bullock cart. K.S. Behera says the magnificent wheels are ‘the crowning glory

of the temple…which imparts a monumental grandeur unique in the realm of art’.

The thin spokes have a row of alternative beads and discs, while the broad

spokes broaden further near the centre where they become roughly diamond-shaped.

In the centre are richly carved medallions, containing numerous deities, erotic

and amorous figures and kanyas in various poses. Similar medallions also

occur on the face of the axle.

The Main Temple, the Surya Deul, consists of two

structures the rekha deul or the sanctum where the image of the deity

once stood, and the assembly hall or jagamohana. It is this structure

that is designed as a chariot of the Sun God.

The deul and jagamohana stand on a magnificent platform,

over 4 m high, with its façade richly carved. Miniature representations of

temple-like structures (khakhara-mundis) are carved in close succession

along the platform. In the niches of these khakhara-mundis are mainly

figures of beautiful women. Erotic couples and voluptuous young women flaunting

their beauty in various stylized postures are other recurring motifs in the friezes

on the platform.

Twelve pairs of colossal wheels are carved on the sides of the

platform. Each has 16 spokes radiating from the axle, with ornately carved

medallions depicting various deities, while the seven horses gallop together

beside a broad flight of steps.

Little remains of the sanctum except for the platform but it does

give an idea of the original structure, which was a square chamber with a shikhara

that rose to over 60 m! Three larger-than-life statues of Surya, called the parasa

devatas, were placed in niches of the temple wall. These statues were so

placed that they caught the Sun’s rays at sunrise, noon and sunset.

The life-size image of Surya in the southern niche stands

majestically on a chariot drawn by seven horses while only the upper torso of

Aruna, the charioteer is shown. Draped in a short dhoti and with feet covered

by long boots, the figure of Surya is heavily bejewelled with a necklace, armlets,

earrings and a short crown, all richly embellished. In his hands are stalks of

fully blossomed lotuses, a characteristic attribute to Surya. Around the head is

a carved halo with tongues of flames at the outer edge. At the crown of the

halo is kriti-mukha flanked on either side by a flying figure blowing a

conch, while around the edges are ten divine dancers all playing musical

instruments. Near Surya’s right foot is the royal donor with folded hands, his

sword kept flat on the ratha. The kneeling figure near the left foot

evidently represents the family priest of the king. While at the extreme ends

are the goddesses of dawn and pre-dawn, Usha and Pratyusha, dispelling darkness

by shooting arrows. The 3.45 m high Surya images in the western and northern

niches are similar in most essential details to the one on the southern nich.

The Jagamohana or assembly hall (or porch) remains the

best-preserved building in the complex. Its extant height is about 39 m. A

cubed structure with a tiered pyramidal roof, it has recessed walls with

opulent carvings. Beautifully proportioned doorways lead inside but the interior

has been blocked to arrest the walls from subsiding.

Two lions, each rampant on a crouching elephant, are in front of

the eastern stairs of the bhoga mandapa; two elephants, richly decorated

and fully harnessed, on the north; and two gorgeously caparisoned war-stallions

on the south, originally guarded each of the three staircases of the jagamohana.

The animals – masterpieces of Odia art, were originally mounted on a partly-carved

platform. The animals on the north and south sides have been re-installed on

new pedestals.

The Aruna Stambha, a free-standing pillar in chlorite with

the figure of Aruna, the charioteer of Surya, on its crown originally stood

between the jagamohana and the bhoga mandapa. Of exquisite workmanship

and elegant proportion, the Aruna Stambha now stands in front of the main gate

of the temple of Jagannath at Puri, moved allegedly to prevent its desecration

at the hands of Muslim invaders.

In front of the eastern steps of the jagamohana, is a

large, pillared hall on a high platform that is approached by a flight of

stairs. This structure, now without a roof, is the Bhoga Mandapa where

offerings were made to the Gods. Some call it the nata mandir (or dance

hall, or festive hall) because of the panels of dancers and musicians chiselled

over the face of its platform, plinth and walls that give the mandapa an

air of permanent celebration.

On the face of the bhoga mandapa platform are carved rows

of khakhara-mundis or niches with sculpted figures, mostly of women and

erotic couples, while on either side of the khakhara-mundis, are female

figures. These women are portrayed in a variety of poses with their arms raised

over the head, holding the branch of a tree or a flower, fondling a child, or

wringing water from their wet hair. Some of the niches near the corners contain

seated dikpalas, guardians of the directions, while some others have

images of deities or even of elephants. Higher up the platform wall is a row of

geese, and another of an army of infantry, cavalry, elephants and

palanquin-bearers in procession.

To the west of the main temple is the Mayadevi Temple,

dedicated to one of the wives of Surya. But in all probability, the temple was

built for Surya, a presumption substantiated by the figures occupying the

niches in the sanctuary. This temple, which archaeologists claim was built

earlier than the Main Temple, was reclaimed from the sand as late as the beginning

of the 20th century. Consisting of a sanctuary and a porch, it is fronted by a

platform and a compound wall made of laterite.

The pedestal inside the sanctum was found empty when the temple

was unearthed. However, according to local lore, the missing image, called

Ramachandi, is now in worship in a temple 8 km from Konark and was removed to

its new abode when the Muslims overran the temple.

In 1956, a small temple, a little over 2 m tall, was discovered

to the southwest of Mayadevi Temple. Facing east, the temple, locally called Vaishnava

Temple, has Vaishnava affiliation and this irrefutably proves that the

worship of deities other than Surya was conducted within the Sun Temple

enclosure.

Hii there

ReplyDeleteNice blog

Guys you can visit here to know more

Konark Sun Temple in Odisha

Thanks for Your Helpful Tips for Konark SunTemple. It Will help Them who are Looking for a best Package from Puri Ya Bhubaneswar To Konark Sun Temple. Konark Sun Temple is one of the most visited tourist places in Odisha.

ReplyDeleteVisit http://travelhelp.co/holiday/ for a best tour package to Konark Sun Temple(Odisha Tour Package)

Thanks a Lot….Keep sharing